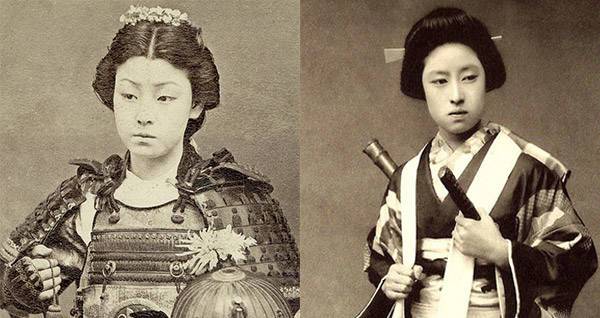

I have been researching the onna-bugeisha, female samurai warriors, and women of the samurai class and that’s when I realised –

History is full of powerful women who have fought, sacrificed and won battles for their lands, however our storytellers have been miser in telling us these stories.

So my curiosity was at its peak when I started reading about Japan’s elite women warriors. Who were these ladies? Which history did they come from? Exactly how did they appear? What functions did they fulfill during the conflicts they engaged in? What tools did they utilize? The men who served beside them, how did they think of them?

One such story that appealed to me was that of Nakano Takeko.

Who was Nakano Takeko?

On 15th January 1847, Nakano was raised during a turbulent period in Japanese history in Edo, Japan (today’s Tokyo). She was the third child of Nakano Heinai, a physician who worked for the northern solid Japanese feudal house known as the Aizu clan.

Takeko was raised in a household of scholars and warriors, and she developed an early interest in combat skills and military planning. Her father urged her to study with the top martial artists in Edo since he was aware of her gifts.

At 16, Takeko was chosen to join the Women’s Army of the Aizu clan, a group of female warriors trained to protect their families and homes during battle. Takeko swiftly rose to become one of the Women’s Army’s most promising recruits, a group of exceptional archers and swordswomen. Takeko mastered the naginata, a long polearm with a curved blade at the end, under her teacher, Akaoka Daisuke. Nakano’s teacher eventually adopted her, and in the 1860s, she collaborated with her as a martial arts instructor. By then, she had also received instruction in martial arts, horseback riding, and archery. Takeko and the other Women’s Army soldiers vowed to defend the Aizu family at all costs, even at the expense of their deaths.

Overview of Boshin Conflict & Nakano’s role in War

Midway through the 1860s, the Meiji imperial dynasty sought to subjugate the Tokugawa family. The civil war arose because many young nobles and samurai opposed the shogunate’s policy of allowing foreigners into the country. The Aizu clan sided with the pro-shogunate side. Nakano wanted to enlist in the Aizu army and fight for the Tokugawa but was prohibited due to her gender. As a result, she organized the Aizu Joshitai, a group of female fighters.

Takeko immediately gained a reputation as one of the most formidable fighters in the Aizu army thanks to her bravery and combat prowess. Her life, however, was tragically cut short in October 1868 during the Battle of Aizu. Takeko led a Women’s Army charge against the adversary lines as the imperial army drew closer to the Aizu castle. Despite her courageous efforts, a bullet to the chest eventually caused her to lose her life.

When the Tokugawa planned to submit to the imperials in 1868, the residents of Aizu stood their ground. This resulted in the Battle of Aizu, where Nakano led her army into conflict despite orders from the imperials to cease fire.

Nakano Takeko Death- Brave Warrior Bids Goodbye

Nakano is thought to have killed about five troops during the battle before being fatally wounded in the chest.

In her last moments, Takeko begged her sister to bury her body deeply to prevent wild animals from defiling it. Her sister complied with her wish and interred her in a private cemetery on the grounds of Aizu castle.

Nakano Takeko’s Legacy

Nakano Takeko’s memory has significantly impacted how female warriors are portrayed in Japanese culture. Numerous pieces of literature, visual art, and film that show strong, brave women in various roles have been inspired by her narrative. Traditional gender norms and prejudices in Japanese society have been challenged by Takeko’s portrayal as an accomplished and fearless fighter.

Takeko’s bravery and selflessness became legendary, and she is still revered as a representation of the strength and tenacity of women. She is often compared to Tomoe Gozen, whose bravery and tenacity typified a real female samurai.

Despite only being 21 when she passed away in 1868, her short life did not lessen the significance of her historical contributions. Every year, at the Aizu Autumn Festival, young girls join the parade wearing hakama (a pleated skirt) and white headbands as a tribute to the bravery of the Joushitai ladies. The tomb and a memorial to her are situated at the Hokai Temple in the western Fukushima County city of Aizubange.

Japanese Way of War

I have long pondered how much Nakano Takeko’s narrative might be based on historical myth. All women of higher social standing would have carried weapons (if covertly) throughout her era, and young girls would have been educated to use naginata to defend their homes. The Imperial Army’s existential danger to the Aizu was probably why it was permissible for an autonomous female combat army to be formed.

Admiral Dewa Shigeto, an Aizu native, referred to Takeko and her contemporaries as the “Joshitai,” or the “young (unmarried) women’s forces,” in the early 1920s, which was the first time they were publicly acknowledged. During the conflict, Shiget was a member of the “Byakkotai,” a reserve youth organization from the Aizu region that is also remembered. He wasn’t old enough to fight; he was only twelve.

Ironically, the fact that Takeko was merely gunned down is what makes her narrative more meaningful to the Japanese mentality. The Boshin War’s Battle of Aizu is renowned for pitting a force founded on traditional notions of honor and devotion against a power primarily based on numerical and technological advantage. Even today, Nakano Takeko’s tale illustrates the intense conflict many Japanese people have between honorable traditions and contemporary utility.

It’s interesting to note the differences in mindset between the older and younger generations of Japanese people. Takeko might have served as a spokeswoman for the forward movement if she had lived in the present. Although female fighters were uncommon in Japan, some were well-known and respected for their prowess and valor in combat. These women displayed incredible bravery and tenacity. They took up arms and fought for their families, territories, and principles. Several of them were in charge of their armies.

Their accomplishments and the legacies they have left behind, have truly inspired me.