The rampant economic exploitation of resources in Niger, one of the poorest countries of the world by France, its former coloniser, is symptomatic of a larger trend of European neo-colonialism demonstrated by France in the poverty stricken continent. As Orano, France’s mining firm has been dismissed out of Niger on Friday, it is important to understand why this is an important point in the collective struggle against colonial remnants.

While being imprisoned by a fascist regime, renowned Italian scholar Antonio Gramsci, wrote about the role of ideas in the establishment of power and regulation. His writings were later compiled into Prison Notebooks published in the 1940’s in parts. It is in these writings that Gramsci reveals to us ; power is asserted through ideas, not by action. The dominant class uses thought instead of brute force to dominate the working class.

A common colour between the picture of a man surviving a fascist regime in twentieth-century Italy and that of a Nigerien baby starving to death next to the French embassy in Niger today is indicative of a peculiar form of deficiency. It is an imposed yet willingly chosen deficiency, strategically inhibiting one from making choices for oneself. Citizens are forced to live in a space which reeks of freedom yet feels like slavery.

According to the World Bank, almost half of the Nigerien population lives below the poverty line. While still using the French currency Franc as a medium of exchange, their economy is on the verge of collapse with one of the world’s lowest HDI rankings. While using the colonial currency called CFA (Communauté Financière Africaine), it belongs to the Franc zone which consists of fourteen other post colonial African states under the same currency owned by France. It is since 1971 that a French mining firm called Orano has been managing almost the entirety of the uranium mining industry in Niger. Over seventy percent of France’s nuclear energy needs are met by this French mining company operating out of Niger.

While Niger grapples with some of the world’s most severe human development crises—such as inadequate access to electricity, alarming rates of malnutrition and starvation, high maternal mortality, and pervasive poverty, French media remains preoccupied with Madam Macron’s sexuality and Jordon Bardella’s sex appeal. With this level of French engagement in Nigerien human development issues, why is it that there are some Nigerien elite like the ousted president Mohammed Bazoum who repeatedly emphasise on cooperation with France? Gramsci would be able to explain in terms of political hegemony.

Gramsci and Hegemony

Antonio Gramsci redefined the function of ideology as it existed in his society. His contemporaries maintained that the ideological superstructure shared quite a mechanical relationship with the economically determined base or the economic components of civil society. Therefore the role of ideology did not pervade the economic realm of ownership/factors of production at all, as the two existed as separate entities – the idea that the amount of currency in one’s pocket did not have anything to do with the soap opera being aired on tele.

In such a system each economic class propounded its own ideology and these discourses functioned within their own water tight compartments. However, Gramsci introduced the concept that the function of ideology which aims to control a population supersedes the physical boundaries of particular economic classes. He told us that the apparently different ideological elements of one economic class could, at any time, be adopted by another one. A strong hegemonic class perpetuated an ideology serving their interests to each member of civil society irrespective of the member’s economic background.

Gramscian thought also introduces the concepts of ‘organic ideology’ propounded majorly by the ‘organic intellectuals’. The task of ‘organic intellectuals’ is to create a ‘hegemonic principle’ which is essentially an ‘articulating principle’ that aims to absorb the subordinate classes into the hegemonic systems socially, economically and politically with relative ease.

Ideology then is not just a strand of a particular discourse, but becomes part of a pervasive atmosphere which facilitates the healthy existence of a hegemonic system – it becomes a total discourse pervading all spheres of civil society. Gramsci tells us that the sustenance of a hegemonic system in any society is perpetuated through the hegemonic class’s control over two things ; economic structures and ideological discourses. It is through a synchronised control over these two entities that the hegemonic class maintains its perpetual control.

Gramsci introduces the concept of ‘Hegemony’ for the first time in his Notes on the Southern Question (1926), where he begins by defining it as a system of class alliance in which a ‘hegemonic class’ leads by exercising political leadership over the ‘subaltern classes’ by ‘winning them over’. It is somewhere within the implications of this phrase of ‘winning over’ that France’s occupation of Africa and the role of grassroots Nigerien rebels as organic intellectuals fits in.

What differentiates Gramsci’s idea of hegemony from other social theory is this – his endeavour to understand the nuanced yet prime role of morality/ideas as drivers of subjugation in society. Due to this prioritisation of mental subjugation over the physical, Gramscian understanding of the organic intellectual, hegemony and hegemonic principles is suitable in order to deconstruct the French colonial attitude visible in Africa today.

Gramsci derives two quintessential conditions for the perpetuation of hegemony. First of all, the ruling or the ‘hegemonic class’ cannot ignore the interests/existence of the other groups over which it exercises its ‘hegemony’, it risks losing its consensus amongst the subordinates if it does. It has to at least acknowledge the interests of subordinate groups. Added to this, the hegemonic class will always have to try to maintain some kind of an equilibrium between themselves and the subordinate groups whereby the hegemonic class will be forced to make some sacrifice of its corporate interests. Secondly, ‘hegemony’ entails both economic leadership as well as ethico-political leadership. In other words, it entails that the hegemonic class be a “fundamental class”–that is, a class situated at one of the two fundamental poles in the relations of production: owner or non-owner of the means of production. It would seem, therefore, that hegemony entails for a class its execution of a leadership role on the economic, political, moral, and intellectual levels vis-a-vis other classes in the system, coupled with the sacrificing of some of its corporate interests as a fundamental class precisely to uphold its vanguard role.

Noticeable in such a hegemonic practice is the abstract notion of balance: in order to establish political leadership by consensus a little amount of economic ambition has to be foregone in contrast to a political leadership established by coercion that does not require narratives, where crude profit maximisation can be utilised. Indeed, this notion underlies Gramsci’s definition of the concept of hegemony, and the notion itself is embodied in Gramsci’s elaborate concept of power.

The hegemonic class tries to exploit the subordinate classes by making it seem like it was their idea in the first place, that the hegemonic class is trying to either revolutionise or standardise the system that governs subordinate groups. It is the sole aim of their hegemonic principle to establish how they are here merely to restore a certain abstract ‘balance’ in civil society, which by all means is in the interest of those who are governed.

Colonial history Of the French ‘pre carre’.

Since France was forced to grant independence to sub saharan African countries in the 1960’s, and the second world war was coming to an end while universal modern democracy emerged as the ideal form of governance worldwide, the driving intellectuals of French political ideology devised a string of political, legal and military policies which ensured to maintain the French hegemony over countries like Niger even after Africa ceased to be treated as a French colony by the rest of the world.

France’s modern preoccupation with postcolonial African states goes back to the 1960s. Most French colonies in Africa experienced decolonisation later than, say, the English or other European colonies. With this late independence, came a virtual inability of the former French colonists to actually let go of their hegemony over these African states. Right after the colonies independence, it was evident that France was finding it a bit hard to let go of it’s beloved ‘pre carre’ in Africa- a term used by 18th century Frenchmen which literally translated into ‘our own square enclosure’, a bit like one’s personal backyard.

Following the world’s lead, as the last bits of colonial Africa were scrambling for independence and a democratic voice, France sought to maintain a lasting political, cultural, economic, and military stronghold over its former colonies in Africa. Amongst other quite problematic reasons, France did so most importantly because of its hegemonic authority in postcolonial Africa – that it was still strong enough to extract huge amounts of natural resources out of the continent at bare minimum prices. Sounds a bit like 18th century British policies in India, is it? Well, they are quite similar indeed; read mercantilism fueled by free human labour under different subheadings in the 21st century.

France decided to preserve its hegemony in its former colony by providing military and technical ‘assistance’ to the newly ‘independent’ African regimes – in return for supporting/cheerleading for the French voice on international forums. Paris thus was quite successful in establishing a type of neocolonial arrangement within these sub-Saharan states of limited sovereignty in the modern world. This African postcolonial reality strained with hegemonic power relations was captured by the term French pre carre in Africa, or France’s exclusive area of action in Africa.

The African colony had always been a cherished asset of the French. It contributed majorly towards the perception of France as being one of the strong powers of the world, it was also one of the reasons why France was able to secure a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council in 1945. Charles De Gaulle, the famous French president who led France out of the second world war and managed its policy during the cold war era, supported France’s occupation in Africa. In fact, he believed that it was imperative for France to maintain control over African polity through building consensus in good faith.

De Gaulle’s ‘policy of grandeur’ which sought to establish France as one of the world powers promoted the perpetuation of a coherent French pré carré, by the use of military force if needed. A hegemonic control over past African colonies was thus one of the aims of De Gaulle’s foreign policy.

The sum of formal and informal French-African partnerships, ventures and lobbies were collectively referred to as Françafrique, a term coined by the first president of Côte d’Ivoire, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, who was also a staunch supporter of the French led development model. He coined the term in 1973 to commemorate this kind of a permanent link between Paris and its former African colonies. It was this ideology rife with paternal hues that determined the French hegemonic principle which makes its appearance even today – Allow us to take ‘care’ of you while we exploit your riches.

Such kinds of paternalistic narrative as a tool to trap past colonies have defined France’s relations with the African states, creating what Gramsci would refer to as a ‘hegemonic state’. Interestingly, this French control was further promoted by the African elite who were eminent parts of the French political landscape in the 1950s and 1960s. For example, one might wonder what purpose would a number of African statesmen serve as members of the French parliament in Europe. The French radical politician Félix Gaillard’s 1957 government included four members born in sub-Saharan African colonies: Modibo Kei’ta, Hubert Maga, Hamadoun Dicko, and Houphouët-Boigny. This is what Gramsci meant by the hegemonic class’s concerted efforts to ‘win the other classes over’. It was through such little diplomatic gestures that the French polity as a ruling class employed a selective political representation as an instrument to create Gramsci’s ‘consensus’ amongst the African people.

Interestingly, although these French political puppets didn’t have much to do with direct French policymaking at all – they were successful in securing an assured presidentship of their respective republics of Mali, Dahomey (present-day Benin), and Côte d’Ivoire. Does that not sound a bit similar to Nawab Mir Jafar from 18th century bengal? Seems like not much has changed in the inner quarters of the white man’s burden hall.

Such pro France African leaders were the main vehicles of normalising the coloniser’s ideology amongst the colonised. Thus such leaders then became fully involved in the creation of an influential Françafrique network. Most bilateral relations promoted by French supporting African leaders were always evidently unequal, especially in terms of military intervention, also often generating discontent amongst the subordinate locals.

This tradition still exists today, as most political leaders and statesmen of the sub saharan group are funded and supported by France. For example, Mohamed Bazoum , who was deposed by a coup in 2023, was famous for being an ardent supporter of French intervention in Nigerien internal affairs.

Another example is that of the ruling Bongo family of Gabon, who have harboured deep and enduring ties with France for generations. Writer/analyst Thomas Borrel terms it as being ‘emblematic’ of Françafrique, a chain of African elites engaged in corrupt practices while helping the French agenda under a vague guise of ‘assistance’, ‘furthering democracy’ or ‘providing military protection’.

Jacques Foccart, a well known businessman and bureaucrat known as “Monsieur Afrique” for his sustained efforts in keeping the former French colonies tight knit was a member of the French hegemonic class. He writes about the intimate relationship of Gabon’s dynastic ruling family, the Bongo’s and French polity in his memoir.

Since the last decade, France’s hegemonic ideology in such erstwhile colonies has been promoted by three main tools – direct monetary control, cultural intervention and extensive military deployments. To gain economic control, France created a ‘Franc Zone’ comprising fourteen African states and mandated them to use the French currency franc de la Communauté Financière (CFA) even after independence from the French colony.

Today a growing number of African states exhibit a determination to rebel against this economic tool of domination. CFA, which literally read as “Colonies Francaises d’Afrique” (French Colonies of Africa) is still used by those fourteen states as a legitimate currency of exchange. With the circulation of French currency in African states, France was able to exert significant economic and political control over the nations as it was the custodian of the currency’s convertibility and monetary policy.

The CFA has been used as one of the primary tools to promote the main French hegemonic idea in African countries – that it is in Africa’s interest to be led by the French. The CFA has been trumpeted by government officials as a mechanism for promoting monetary stability for years. The French as well as their political mouthpieces in Africa have claimed that transferring their economic reigns over to the French would actually result in facilitating economic integration for all the African states, and improve their overall economic performance.

This group which supports the usage of the CFA in present day pitches typical hegemonic narratives – to be pegged against the Euro helps stabilise African economies and fight inflation. The usage of CFA has also been defended on the basis of a lack of alternatives, that a sudden change to African currency would hurt these already fragile economic systems.

This is where the role of organic ideology, as defined by Gramsci to be a force acting against hegemonic governance comes in. There have been a number of coups in African states which have espoused a more decentralised approach to power sharing. For example, Senegalese economist Ndongo Samba Sylla explains in an interview that the main aim of the CFA is not to improve/stabilise African economies but instead protect the French currency against the rise of the American dollar. He says to Al Jazeera, ‘From a purely practical economic standpoint, the CFA is not a beneficial currency or system for its user states’.

It is to be noted that in Niger, French remains the official language for 25 million Nigerien citizens. Apart from the paternalistic French attitude, another hegemonic principle has been effectively employed by the former colony to maintain its political hegemony over Niger. France has been at the forefront of promoting the notion of it being the ‘Gendarme of Africa’ i.e security force of Africa. It has self qualified itself as Africa’s trusted military aid against terrorist insurgents such as al-Qaida in the vast Sahel region, which includes a dozen countries from Eritrea to Senegal, via Niger. As Gramsci predicts, the hegemonic class strategises to ‘maintain balance’, in this case fight terrorism, in order to again impose its own hegemony by legitimising its unnecessary military presence.

These peculiar French strategies, disguised as naive ‘aid,’ have over time not only garnered suspicion and rejection due to their underlying colonial mentality but have also spurred Nigerien and many other grassroots organic intellectuals to develop a counter-ideology to challenge hegemonic narratives. As the current government spokesperson of Mali has characterised France’s hegemonic games as ‘neocolonialist, condescending, paternalist and vengeful policies’.

France exploited Nigerien uranium mines

France has exploited Nigerien Uranium mines since the 1960’s. The French do not believe that such exploitation of resources from a former colony is unethical. Instead of being ashamed, they either disown the facts or state the truth quite nonchalantly, as if it’s one of their rights as erstwhile colonisers to use its colony. One of the most prominent media houses of France, Le Monde quotes, ‘A natural resource essential to the operation of French nuclear power plants, uranium mined in Niger has been exploited for over four decades by the French nuclear fuel cycle group Orano (formerly Areva).’

Orano (formerly known as Areva) is a French multinational company specialising in nuclear energy. However, it is not just a corporate firm trying to earn money – it is way more than that. Ninety percent of Orano is in fact, owned by none other than the French state itself. The French state has set up three firms in order to mine uranium in Niger. The Aïr mines are based near the town of Arlit in the desert to the north of Niger.

The Akokan mining site is situated about ten kilometres from Arlit. This one has been closed since the end of March 2021 as France has already exhausted all of this site’s uranium reserves. Third in line comes the Imouraren mine – considered to be consisting of the world’s largest uranium deposits. There are a couple of serious questions which arise out of images of such rigorous resource depletion in the name of vague promises like ‘democracy’, ‘assistance’ and ‘protection’.

Where is the extracted uranium actually going?

Do the Nigeriens have any right over their own resources?

What is the reason behind Niger’s developmental inability to use uranium as well as Europe can?

How much money are the French paying to compensate for finishing Niger’s natural reserves?

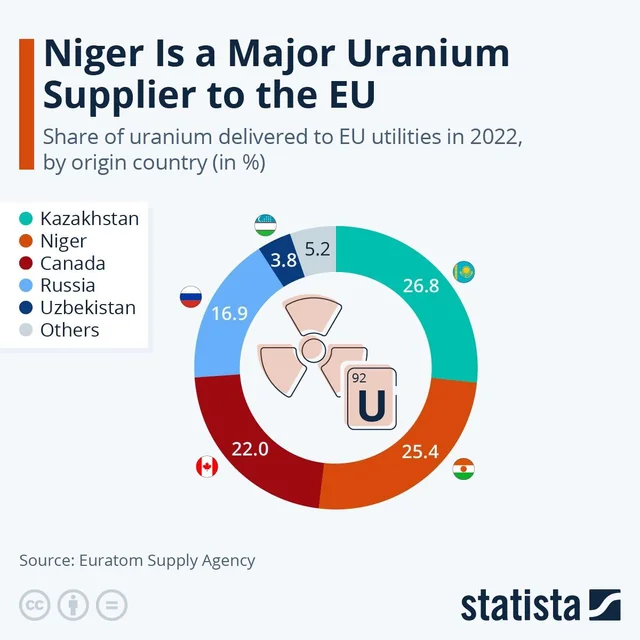

Unfortunately, all the answers legitimise France’s clear colonial intentions. According to the French government’s nuclear officials, Niger’s uranium has been indispensable for the generation of energy in France. Along with bearing the cost of French energy, Niger is also the second largest supplier of energy for the European Union. Niger being one of the top suppliers of uranium to France, does not receive a proportional payment in return due to their post colonial status. It was till 2014 that the uranium royalties received by Niger were half as much as compared to the ones received by countries contributing way lessuranium, like Australia and Canada, which are not former French colonies.

According to the World Bank, only about 6-7% of the local population survives with access to electricity. However, one in every three lightbulbs is lit in France, powered by energy generated from uranium sourced out of Niger.

While most French people revel in comfortable homes and the official website of the French mining company puts out statements like, ‘ … continuity of uranium mining operations in northern Niger is the cornerstone of Orano’s mutually beneficial relationship with Niger.’

It is only quite recently that questions have been raised in Africa. It is the organic intellectuals who are questioning the value of this supposedly ‘mutually beneficial relationship’ that has rendered Niger to rank 189th out of 191 countries in the 2021 HDI Index.

Way Forward

After decades of exploitation, the locals have decided to create their own ideology and resist the colonial thrust coming from Europe and French supporting local elites. Niger is one of the many African states which has begun using coups as a way of resistance against colonial rule. Along with former French colonies like Burkina Faso and Mali, Niger has demonstrated a strong determination to fight against French hegemony.

Orano’s operating permit for a large uranium mine has been revoked by the rebels since Friday. Orano said on Thursday that it had been ordered out of the Imouraren mine in northern Niger which sits on an estimated 200,000 tonnes of the metal, used for nuclear energy and weapons.

The most favourable outcome of all this would be for Niger and other African states to shake off French hegemony, reject colonialism and opt for a democratic future. Although Niger and its fellow former colonies should seek lessons from the independence of other colonies like India and how they navigated their way since European departure, the path to overthrowing a hegemonic class and establishing an egalitarian society is not going to be an easy matter.

Whether revoking Orano’s permit to extract further resources from Niger will be a small point in a larger scheme of pushback or the end of the struggle, only time will tell. However, the message has been put across in an audible voice – the white man is worrying about the weight of his burden as you read.