In the early 2020s, the world is facing an intense battle between democratic and authoritarian values. Democracy – “rule by the people” in Greek – is a government system where citizens elect and decide on leaders and laws freely, using frequent elections and open discussion. It is dependent on checks and balances (rule of law, independent judiciary, free media) to guard individual rights and against abuses.

Conversely, authoritarianism holds power within the control of one individual or a limited group of ruling elites. Authoritarian governments restrict political pluralism and popular participation, generally censor the media, and resort to repression to maintain the status quo. Empirically, democracies permit extensive citizen participation and regime change, whereas authoritarian governments closely regulate dissent and regime change. Between these poles are hybrid regimes (often referred to as “illiberal” or “competitive authoritarian” regimes) that conduct elections but rig them to maintain power.

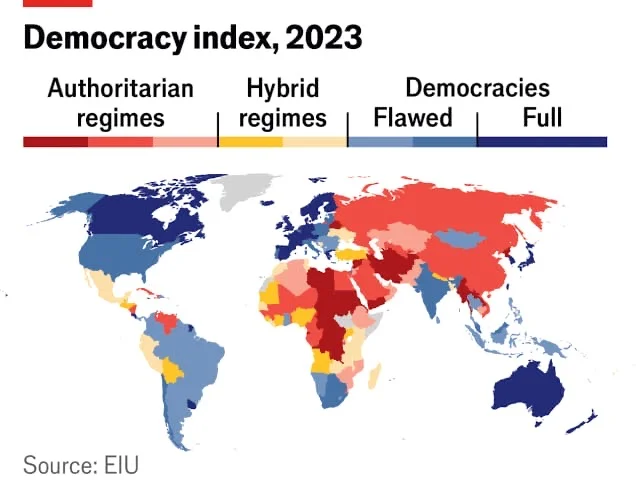

Over twice as many nations have been trending toward authoritarianism rather than toward democracy in recent decades, states International IDEA’s 2022 Global State of Democracy report. Freedom House also reported the 15th consecutive year of decreased freedom worldwide by 2020–2021. Simply put, democracies are under pressure all over the world while authoritarian governments become increasingly assertive.

Even in the United States, which has been a bastion of democracy for so long, recent years saw ominous signs of decay. The U.S. Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court continue to be elected, but institutions of the United States have been strained by intense political polarization. Hateful rhetoric and assaults on the free press by American leaders (particularly in the Trump administration) “undermined the country’s ability to persuade other governments” to uphold human rights, and were “actively exploited by dictators” overseas. The January 6, 2021, storming of the U.S. Capitol – when rioters attempted to stop a legal transfer of power – reminded many just how brittle democratic conventions can become.

Popular Resistance and Protest Movements

In Myanmar, soldiers overtook the government in February 2021 and imprisoned the democratically elected officials. Millions of Burmese returned in kind with huge Civil Disobedience Movement protests and walkouts nationwide. Protests in Myanmar have regularly been met with bravery and the iconic three-finger salute; as ominous as the situation has become, civilians still resist.

In Hong Kong, a one-time half-autonomous territory, massive pro-democracy protests in 2019-2020 broke out against Beijing’s tightening grip. Ever since, Beijing has enforced a draconian security law. In late 2024, for instance, forty-five prominent Hong Kong democracy activists (ex-legislators, protest organizers, scholars) were sentenced to as many as ten years behind bars just for holding a peaceful primary election in 2020. Human Rights Watch alerts that Hong Kong’s “civil liberties and the rule of law have nosedived” since the crackdown by Beijing, with independent media and political parties being compelled to shut down.

The Middle East and Africa have witnessed similar challenges. In Sudan, a long-time location of military strongman leadership, civilians once more poured into the streets. Following a 2021 coup by the military that burst asunder a tentative transition to civilian governance, Sudanese protesters demonstrated for democracy. They were subjected to internet shutdowns and frequently deadly force – one report observed security forces shoot and kill 15 protesters on a single day in late 2021. Organizers, however, promised an “open escalation” of protests until the coup leaders resigned. In most neighborhoods of Khartoum, civilian resistance committees organize protests the same way they did to bring down President Omar al-Bashir in 2019.

In Latin America, it is a mixed picture. There have been waves of popular discontent with governments in some nations. In Cuba, for the first time in decades, spontaneously, thousands of people protested in July 2021 against economic troubles and restrictions on freedom. The government did not delay; hundreds of protesters were arrested, and the American government sanctioned Cuban officials for the suppression.

In Chile, huge protests in 2019 against inequality gave rise to a new constitution-making process, regarded as a democratic triumph. In Brazil, tens of millions tuned in to the corruption trials news and subsequently voted out President Bolsonaro. Yet, populist strongman discourse continues throughout the region – for instance, Mexico’s government is accused of undermining democratic accountability while still being formally democratic.

Democracy vs Authoritarianism: Implications for Rights and World Affairs

The outcome of this global tug-of-war has profound consequences for human rights, economic development, and international stability.

On human rights, democracies are more likely to guarantee a wider array of freedoms. As Britannica indicates, democratic governments preclude rule by autocrats and “guarantee fundamental individual rights,” allowing greater personal liberty and equality. Democracies generally safeguard freedom of speech, assembly, religion and the press, enabling minority opinions to be expressed. Authoritarian regimes systematically deny these freedoms. The 2024 Hong Kong mass trial is just one stark illustration pro-democracy leaders were jailed for conducting a peaceful election primary, highlighting how Hong Kong’s previously guaranteed freedoms have disintegrated. In much of the world’s autocracies (from the Middle East to Asia to Africa), activists and journalists get thrown into jail, tortured, or killed just for voicing their opinions. Freedom House has documented that in nations trending toward authoritarianism, “activists faced heavy jail sentences, torture, or murder.”

In international affairs, the democracy-authoritarian distinction frequently organizes alliances and conflicts. Democracies are likely to construct clubs and alliances (e.g., NATO, EU, democratic trade agreements) on the basis of common values. There is even a pattern known as the “democratic peace” – democracies seldom fight each other. Authoritarian powers, on the other hand, might seek national interests more unilaterally or expansively. For instance, Russia’s current regime (authoritarian) is fighting in Ukraine, and China (authoritarian) is enforcing military and economic dominance in the South China Sea and around Taiwan. As an alternative, democratic nations have generally solved conflicts through diplomacy and international law – although there have been exceptions.

Conclusion

On one side are democratic values – popular participation, human rights, and accountable government. On the other hand are authoritarian models – centralized control, restricted liberties, and often nationalistic aims. In recent years, we’ve seen both serious challenges to democracy and inspiring acts of resistance. From the U.S. Capitol to Minsk streets, from Beijing power halls to Hong Kong and Bengaluru cafés, citizens are arguing about the kind of society they desire. What is certain is that the struggle between authoritarianism and democracy is international, complex, and finally a battle over core human values – a struggle that will continue to define our lives for years to come.

Article by Shaloo Singh